Critics of NATO’s war against Libya list civilian casualties, oil greed, uncertain rebel leadership, and persecution of resident sub-Saharan Africans among their objections. At first blush, the targeting of Libya, alone among rebellious Arab states, is odd. After economic sanctions were lifted in 2004 and diplomatic recognition restored, Washington was dealing with Libya.

Arab upheavals led to recalculation. Ghanaian columnist Prince Akyeampong recently suggested Libya represents the threat of a good example. Living standards, he notes, are unmatched in Africa. Measures of health and educational outcome are high, families receive subsidies from oil revenues, and new infrastructure serves people’s needs. Ghanaians quiet on Libya are “Uncle Tom[s],” he says. They “obey their NATO masters.”

Indeed, the United Nations’ Human Development Index ranks Libya 55th in the world, tops in Africa, and 4th place in the Arab world, behind only three rich Persian Gulf states. From 1980 to 2009, infant mortality dropped from 70 per thousand live births to 17; life expectancy rose from 61 to 74 years. Malnourishment fell below 5 percent that year, adult literacy approached 90 percent; youth literacy, almost 100 percent. Primary school enrollment was 97 percent for boys and girls alike; 52 percent and 57 percent of age-appropriate males and females, respectively, attended college.

Libya was free of foreign debts and possessed $150 billion in overseas assets. The Muammar Gaddafi government used the African Investment Bank, located in Libya, to provide no interest loans for African developmental projects. Gaddafi had called for a gold-backed African currency.

With the onset of war, NATO nations confiscated $100 billion in Libyan assets, those funds to be loaned, not returned, to pay for post-war reconstruction. Airstrikes destroyed electrical generation and water facilities, government buildings, civilian housing, and factories.

Iraq too was managing its own affairs. Saddam Hussein’s government nationalized oil production in 1972. With new wealth applied to people’s basic needs, Iraq’s standard of living was tops in the Middle East in 1990. An increasingly urbanized population benefitted from low unemployment, schools worthy of UNESCO commendation, and free health care for the vast majority. Infant mortality and illiteracy rates were low. Women had rights and held high positions in businesses and government.

By 2007, however, U.S. economic sanctions and war had undone these achievements. Mortality rates for younger Iraqi children had moved from 50 to 125 per thousand live births per annum. Iraqi people enjoying access to clean water fell from 90 to 30 percent. Access to sewage systems was 20 percent. Illiteracy rates dropped 25 percent, and unemployment approached 70 percent. Iraq’s 2009 poverty rate was 22 percent, figured at monthly family earnings of $67 or less.

U. S. wars in Libya and Iraq convey three messages to affected populations: Your wealth and resources are ours, your lives do not concern us, and you can’t do anything about it. The message to any and all is that standing up for national independence and for meaningful, safe lives is dangerous.

Recent Yugoslavian history demonstrates this last teaching point. Yugoslavs had experienced decades of state planning resulting in health care and education for all and universal access to public transportation, housing, and utilities. By 1980, a 72 year life expectancy in the multi-ethnic nation exceeded that of the United States. Yugoslavia became an economic power.

During the 1980’s, however, international debts impelled the government to back off from defending hard-won rights. Unions and popular movements rose up and continued with protests after the Soviet Bloc collapsed in 1991. The Serbian government of Slobodan Milosevic collaborated with European and U.S. power brokers, using ethnic divisions to blunt opposition. Milosevic’s usefulness ended in 1997 following electoral defeats and weeks of labor-led, anti-government demonstrations. The U.S. government had been channeling economic aid to breakaway states.

NATO forces bombed Serbia in 1999 for 79 days. Bombs hit public and private housing, roads, bridges, factories, power stations, water systems, hospitals, and schools. Around 500 civilians died. For analyst Michael Parenti, the purpose of the assault was to create “a world in which capital rules supreme with no labor unions to speak of; no prosperous, literate, well-organized working class with rising expectations; no pension funds or medical plans or environmental, consumer, and occupational protections.”

NATO and/or U.S. take-down of governments visibly, successfully, and independently serving people’s needs is obvious, as unsavory as Libyan and Iraqi regimes may have been. Explicit articulation of policies aimed at knocking off regional models of independence is more obscure. But in a different setting, employers do benefit from a “reserve army of the unemployed,” and rarely say so. Peoples and employed workers alike are supposed to sense, on their own, the precariousness of their respective situations and remain docile.

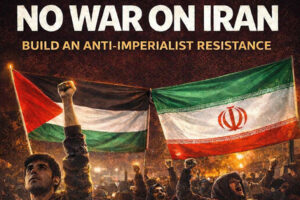

Popular odium at NATO’s brutal history is percolating. Many of those unenthusiastic about empire and capitalist domination are preparing for demonstrations on Chicago’s streets as one way to greet NATO leaders meeting there in May 2012.

Photo: NY Times, 19 June 2011

_________________________